The Hidden Dangers of Index Funds

There are plenty of good reasons for owning passively managed funds. But that doesn’t mean index funds are flawless -- or harmless.

Unless you’ve been stuck on a deserted island for a long time, you probably know that index funds are hugely popular. Investors have been pouring money into low-cost, passively managed mutual funds—as well as into exchange-traded funds, which are typically unmanaged—for the past decade. All told, nearly $5 trillion sits in index mutual funds and ETFs today.

The draw, beyond the low fees, has been performance: Funds that track broad market indexes have outpaced, for the most part, their actively managed counterparts in recent years. The numbers are sobering: Over the 10-year stretch that ended in 2015, 82% of actively managed large-company stock funds lagged Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. Active managers of midsize- and small-company stock funds fared even worse: 88% (in both cases) failed to outpace the S&P MidCap 400 and the S&P SmallCap 600 index, respectively.

But this headlong rush into index funds may mean that some investors are overlooking some of the risks that come with a strategy of merely seeking to match a market barometer. What hidden dangers lurk inside your index fund?

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

They aren’t as static as you think, and that can lead to higher transaction costs.

Indexes are constructed and then left alone for the most part, right? Not really. Even the S&P 500, which is weighted by market value and is not rebalanced, undergoes 20 to 25 changes in an average year as companies are added to and removed from the index, according to a study by Jeffrey Wurgler, a professor at NYU Stern School of Business.

Some indexes, especially the so-called smart-beta benchmarks that have been created for ETFs, may experience a greater number of shifts. The turnover ratio for SPDR S&P 1500 Momentum Tilt ETF (symbol MMTM) is 70%, almost double the turnover of a typical large domestic-company ETF. The fund follows an index that rebalances quarterly. By contrast, SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY), which, as the name suggests, tracks the S&P 500 itself, has a turnover ratio of just 3%.

The problem with turnover, of course, is higher transaction costs. Smart-beta funds, says David Nanigian, a professor of finance at California State University, Fullerton, are more prone to higher trading costs because they reconstitute their portfolios more often than do their traditional index fund counterparts. Smart-beta funds follow strategies that stray from the traditional indexing strategy of weighting securities by market value. A smart-beta fund may, for example, weight stocks equally, it may invest only in companies with revenue or earnings forecast to grow more than 10% a year, or it may only hold firms that have raised dividends consistently over time.

They buy high.

This applies more to funds that track traditional indexes, such as the S&P 500, which is oriented toward large companies, or the Russell 2000, which tracks small-company stocks. When an announcement is made that a new company is joining the S&P 500, its stock price typically jumps about 10%, says Michael Finke, a professor of personal financial planning at Texas Tech University. “Demand drives prices higher,” says Finke.

They track obscure indexes.

Although ETFs and index mutual funds are designed to be transparent, some are built around indexes that are, well, not transparent. Global X Millennials Thematic ETF (MILN), for instance, tracks a proprietary index of companies that stand to benefit from the rise in spending power of millennials (defined by the fund as those born from 1980 to 2000). Frankly, the strategy sounds more active than passive. It certainly doesn’t sound like rules-based indexing. For now, the fund’s top holdings include Amazon.com, LinkedIn and Facebook.

They can hold different stocks than their names suggest.

SPDR S&P Homebuilders (XHB) sounds as if it holds only home-building stocks. But actually, less than one-third of its assets are in builders, says Todd Rosenbluth, an ETF and mutual fund analyst at S&P Global Market Intelligence. Homebuilder also holds stocks in appliance makers such as Whirlpool, furnishings retailers such as Williams-Sonoma and personal-products maker Helen of Troy.

They can switch indexes when they want to.

A fund won’t change its index without informing shareholders, but switching benchmarks does happen. In 2012, Vanguard, the big kahuna of indexing, changed the underlying bogey for 22 of its index funds. The firm switched six foreign-index stock funds from MSCI bogeys to benchmarks provided by FTSE and moved 16 U.S. stock and balanced index funds to benchmarks developed by the University of Chicago’s Center for Research in Security Prices. In May, Guggenheim changed the index behind two of its ETFs: Guggenheim Spin-Off ETF (CSD) and Guggenheim Timber ETF (CUT). “An index change will result in different holdings,” says Rosenbluth. Indeed, by dropping an MSCI benchmark in favor of one from FTSE, Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index Fund (VEIEX) dropped South Korean stocks from its portfolio because FTSE considers South Korea to be a developed country rather than an emerging nation.

They are diversified, but they may not offer shelter from a bubble.

Because of the way traditional indexes are structured—the bigger the company, the bigger its weight in the benchmark relative to other stocks—they can leave you more vulnerable to bubbles, which inevitably burst. In 1999, at the height of the Internet craze, for instance, technology stocks made up nearly 30% of the S&P 500. (By 2002, tech stocks made up just 14% of the index; today, the allocation is back up to 20%.)

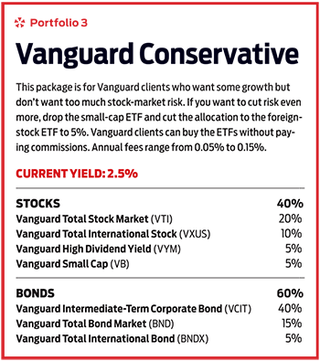

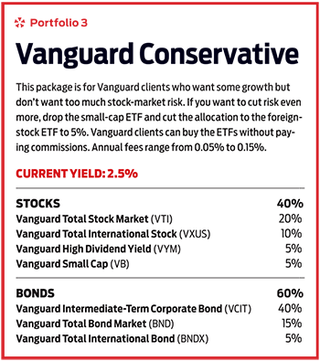

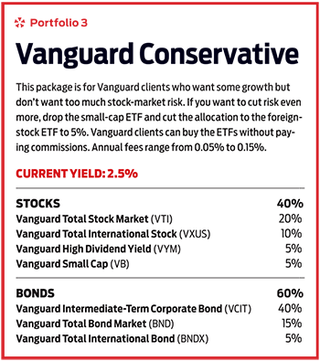

All told, investors should be aware of these risks, but not necessarily wary of all index funds. Says Finke, “It’s not that you shouldn’t invest in index funds. But you might want to consider investing in more than one index. And consider moving beyond the popular indexes, such as the S&P 500.” At the very least, he suggests, think about investing in a fund that tracks a total stock market index, such as Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI). About 28% of the fund’s portfolio is invested in midsize- and small-company stocks.

Nellie joined Kiplinger in August 2011 after a seven-year stint in Hong Kong. There, she worked for the Wall Street Journal Asia, where as lifestyle editor, she launched and edited Scene Asia, an online guide to food, wine, entertainment and the arts in Asia. Prior to that, she was an editor at Weekend Journal, the Friday lifestyle section of the Wall Street Journal Asia. Kiplinger isn't Nellie's first foray into personal finance: She has also worked at SmartMoney (rising from fact-checker to senior writer), and she was a senior editor at Money.

-

Strategies to Optimize Your Social Security Benefits

Strategies to Optimize Your Social Security BenefitsTo maximize what you can collect, it’s crucial to know when you can file, how delaying filing affects your checks and the income limit if you’re still working.

By Jason “JB” Beckett Published

-

Don’t Forget to Update Beneficiaries After a Gray Divorce

Don’t Forget to Update Beneficiaries After a Gray DivorceSome states automatically revoke a former spouse as a beneficiary on some accounts. Waivers can be used, too. Best not to leave it up to your state, though.

By Andrew Hatherley, CDFA®, CRPC® Published

-

Stock Market Today: Dow Slips After Travelers' Earnings Miss

Stock Market Today: Dow Slips After Travelers' Earnings MissThe property and casualty insurer posted a bottom-line miss as catastrophe losses spiked.

By Karee Venema Published

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Stabilize After Powell's Rate-Cut Warning

Stock Market Today: Stocks Stabilize After Powell's Rate-Cut WarningThe main indexes temporarily tumbled after Fed Chair Powell said interest rates could stay higher for longer.

By Karee Venema Published

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Reverse Lower as Treasury Yields Spike

Stock Market Today: Stocks Reverse Lower as Treasury Yields SpikeA good-news-is-bad-news retail sales report lowered rate-cut expectations and caused government bond yields to surge.

By Karee Venema Last updated

-

Stock Market Today: Nasdaq Leads as Magnificent 7 Stocks Rise

Stock Market Today: Nasdaq Leads as Magnificent 7 Stocks RiseStrength in several mega-cap tech and communication services stocks kept the main indexes higher Thursday.

By Karee Venema Published

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Tumble After a Hot Inflation Print

Stock Market Today: Stocks Tumble After a Hot Inflation PrintEquities retreated after inflation data called the Fed's rate-cut plans into question.

By Dan Burrows Published

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks End Mixed Ahead of Key Inflation Reading

Stock Market Today: Stocks End Mixed Ahead of Key Inflation ReadingEquities struggled before tomorrow's big Consumer Price Index report.

By Dan Burrows Published

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Closed Mixed in Choppy Trading

Stock Market Today: Stocks Closed Mixed in Choppy TradingVolatility returned as market participants adjusted their expectations for rate cuts.

By Dan Burrows Published

-

Stock Market Today: Stocks Rally After Blowout Jobs Report

Stock Market Today: Stocks Rally After Blowout Jobs ReportStocks soared into the weekend as investors brushed off strong payrolls data and lowered rate-cut expectations.

By Dan Burrows Published